To repeat the intro to my previous posts on this subject …. Many of the migrant waders – or shorebirds as they are also known – display the most Jeckyll and Hyde characteristics of all birds, living two dramatically different lives and spending time in habitats which are far removed from each other.

Separating these two lives are amazing journeys that take these small yet hardy birds halfway across the world – and back again.

South African birders get to know migrant species during their stay in the southern hemisphere, typically during the months from October to April, so let’s find out a bit more about their ‘other’ lives by delving (again) into the typical annual life cycle of these waders.

This time it’s the –

Wood Sandpiper (Bosruiter) Tringa glareola

Affectionately called ‘Woodies’, this species is so named because they breed on swamps and peat bogs in the coniferous taiga forests of the Northern Hemisphere – who would have thought this is also a ‘Forest bird’ !

Identification and Distribution

Identification of the Wood Sandpiper is relatively easy – compared to some of the other LBW’s (Little brown waders) – and is often the first wader that novice birders will get to know as it is one of the most common freshwater waders

What to look out for –

- medium size (19 – 21cm; 55 – 65g) slim, fairly long-legged, graceful

- straight bill about the same length as the head, white brow extends behind eye

- grey-brown above with eye-catching white ‘spotting’ , grey below

Distribution –

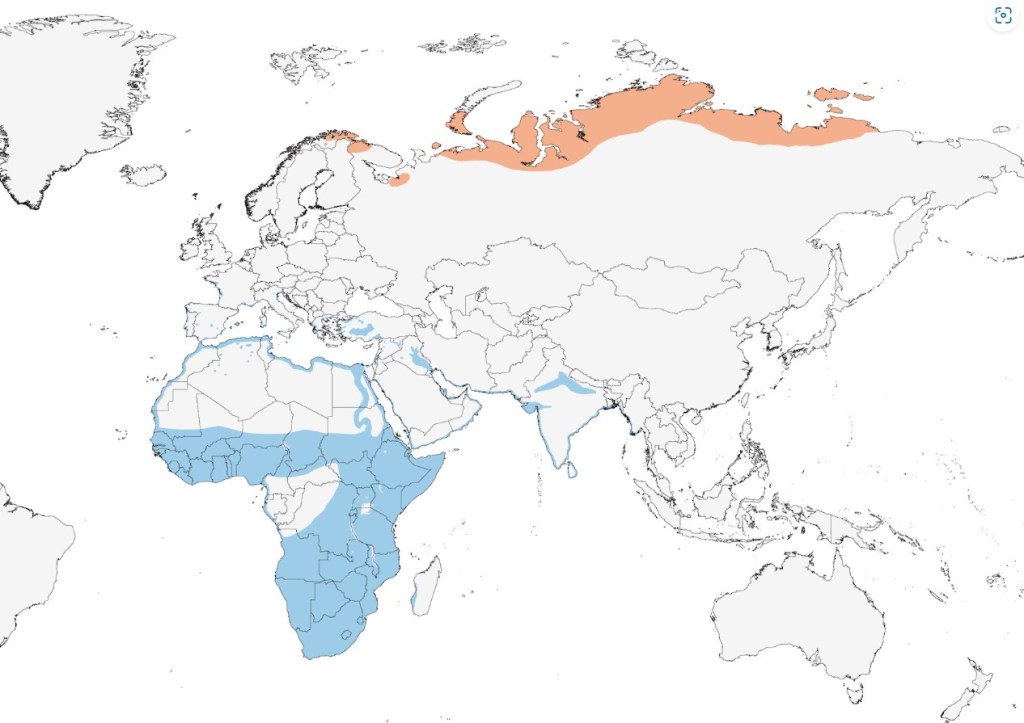

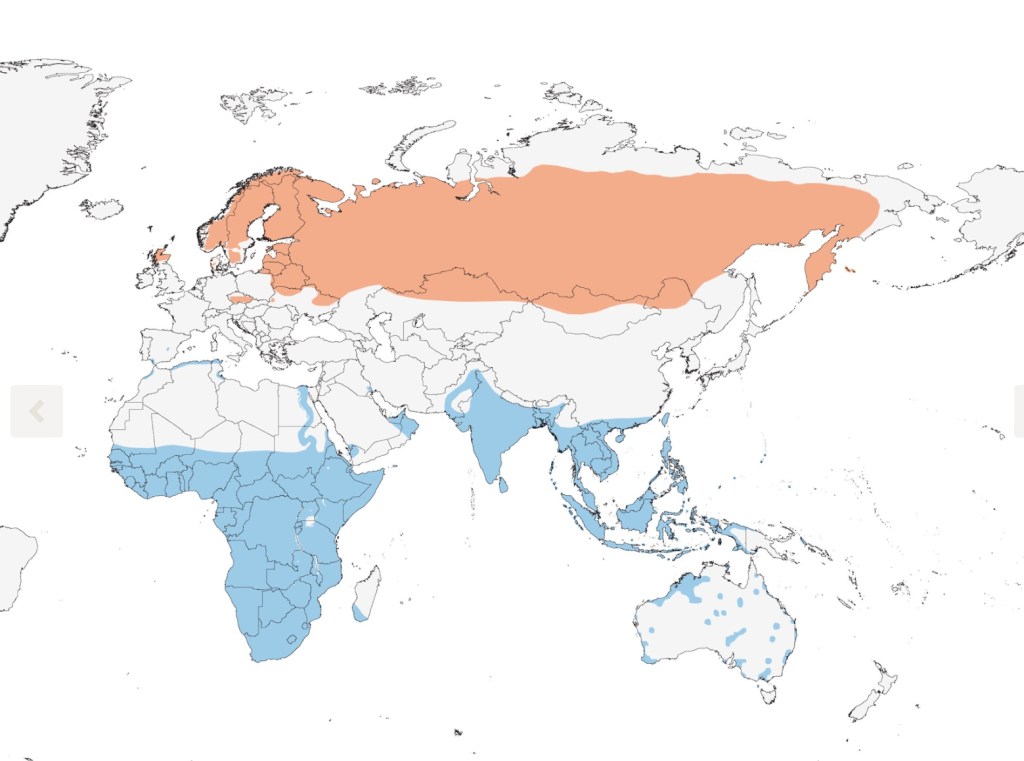

The orange area on the global distribution map (from Cornell Birds of the World) shows where breeding occurs in the Northern Hemisphere while the blue area, mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, is where they go to ‘get away from it all’ and prepare themselves for the next round of raising a family.

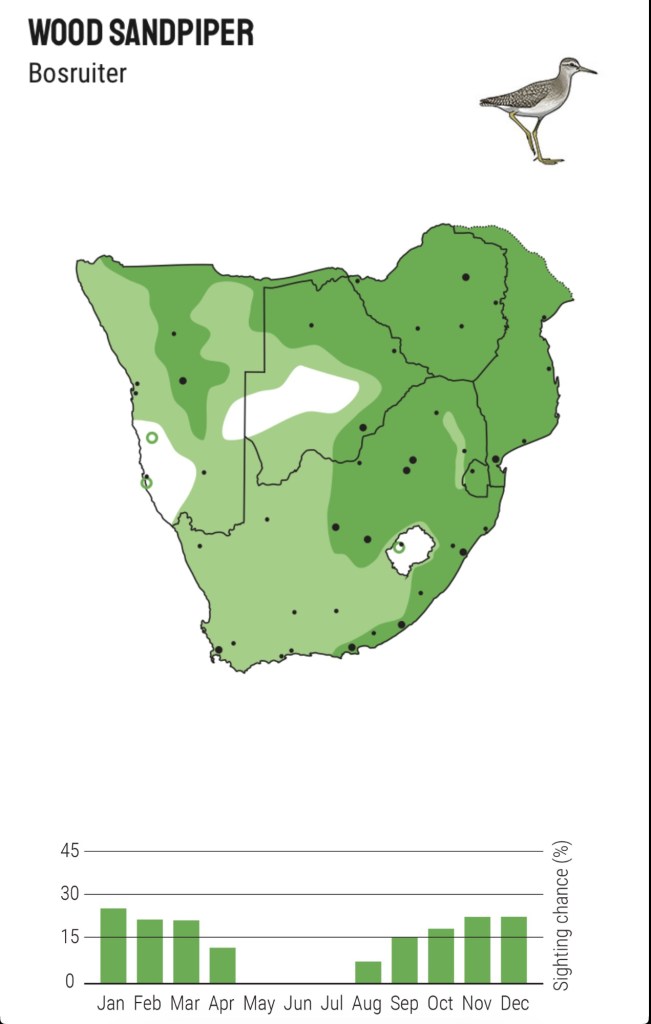

The southern African distribution map (from The Firefinch Birding app) shows the species presence across most of the region but absent from the Kalahari and arid west.

Life in the North

The preferred breeding habitat is the open swampy area and peat bogs in coniferous forests, scrubland between those forests and tundra

Their diet is mainly small aquatic insects, caught by pecking or probing while walking in shallow water

Breeding

The nest is usually a small scrape on the ground lined with moss, stems and leaves, in dense vegetation, but also frequently in trees in old nests of other species

Eggs (usually 4) are laid and incubated for about 3 weeks – from 7 to 10 days after hatching the male cares for the young on its own

Fledging some 3 to 4 weeks later, the fledglings are independent soon thereafter, facing the many dangers that young birds are subject to.

Migration

The birds we see in Southern Africa are thought to originate from Russia, first adults leave early July, arriving in the south from late July / August with juveniles following mainly in September and October.

Migration is undertaken at night with birds capable of single flights of up to 4000km. Overland routes are followed by small flocks or singly, mainly via the Rift Valley

Life in the South

Of the 3 million+ Woodies that head to Africa, some 50 – 100,000 end up in southern Africa, where they seek out suitable freshwater habitats. These can be anything from shallow sewage ponds to marshes, flood plains and muddy edges of streams and rivers, down to the size of a puddle.

Sometime after arrival, adults start a post-breeding moult which continues for up to 4 months, during which time all feathers are replaced with new ones.

Generally, a solitary bird except where food is abundant when they may gather in loose groups

They start departing from late February with the majority having left by end April, heading north to their breeding grounds where the cycle will start all over again…

References : Cornell Lab of Ornithology Birds of the World; Roberts VII Birds of Southern Africa; Firefinch app, Collins Bird Guide; Waders of Southern Africa