The Routine

We had four full days to make the most of our breakaway to this delightful park and we soon settled into a routine which we followed more or less on each of those days. Let’s just say we were out to relax as much as possible, while not missing out on what Addo has to offer.

The mornings were the most relaxed part of the day, getting up late-ish, having coffee while enjoying the birdsong and spending the rest of the morning out on the deck, then venturing out for a drive along one of the routes, usually with a light picnic lunch packed.

This took us to mid-afternoon when we would return to camp, just in time for a rest (I told you we were out to relax!). More deck sitting, followed by getting the braai fire going for the evening meal to round out the day.

Day 1 and 2 Highlights

Stoepsitting

Stoepsitting (relaxing on the deck) is especially rewarding in Addo’s Main Camp where the chalets are surrounded by trees and shrubs which are a magnet for a number of birds.

It almost seems as if the birds that visit the surrounding bushes and trees are prompted by a stage director to appear ‘on stage’, play their part and leave again

Some of the regular “performers” :

Southern Boubou, looking like he is in charge, giving a raucous call just in case you don’t notice him the first time

Greater Double-collared Sunbird, resplendent in green cloak and bright red waistcoat and showing off its colours at every opportunity

Bar-throated Apalis, perky and loud, flitting about the bushes, allowing very brief glimpses as it moves through the foliage – so brief I didn’t manage to get a photo this visit so have included this one from a previous trip

Cape Robin-Chat, haughty and superior – but who wouldn’t be if you could sing as well as it can

Streaky-headed Seedeater, looking a little miffed about no longer being known as a Canary (except in Afrikaans) but singing like one nevertheless

Karoo Prinia, another busy bird not sitting still for long and with an almost desperate look in the eye – perhaps it’s thinking about a thorny issue of some kind …

The Drives

Our drive on day one was limited to a late afternoon exploration of the roads nearest to the camp. At the first waterhole we found a small group of elephants quenching their thirst, while a Warthog approached carefully to see if he could get a look in.

On day two we felt like a longer drive and set off late morning, taking the road southwards to Jack’s Picnic spot where we had a light lunch of fruit salad and yoghurt and the tea that we had prepared before leaving. Jack’s is unique in that it has a number of individual picnic tables each set in an alcove shielded by bush almost all the way around, creating a cosy, private space to enjoy your picnic.

On the way we had encountered several groups of elephant – some at the waterhole, others nearby.

While watching the wild life activity at Hapoor waterhole near the picnic spot, we witnessed a mixed herd of elephants approaching at a pace, tails literally flying in the air – clearly they had one thing in mind – to quench their thirst on a hot day

An older elephant lagged behind – the pace just too fast for it (I can relate to that)

A few Zebras in the bushy areas added some variety to the drive

Ever on the lookout for birds, here are those that caught my camera’s eye

A pair of African Pipits were enjoying the wet open veld where it had just rained, pretending to be waders for a few moments

Joining the Pipits was a bird that at first had me wondering due to its wet and bedraggled plumage but a study of the photos I took convinced me it was a Karoo Chat – probably a juvenile

Gerda is always on the lookout for wild flowers – there was not much to see but we did come across a single Spekboom that had flowers, while thousands of its like had none

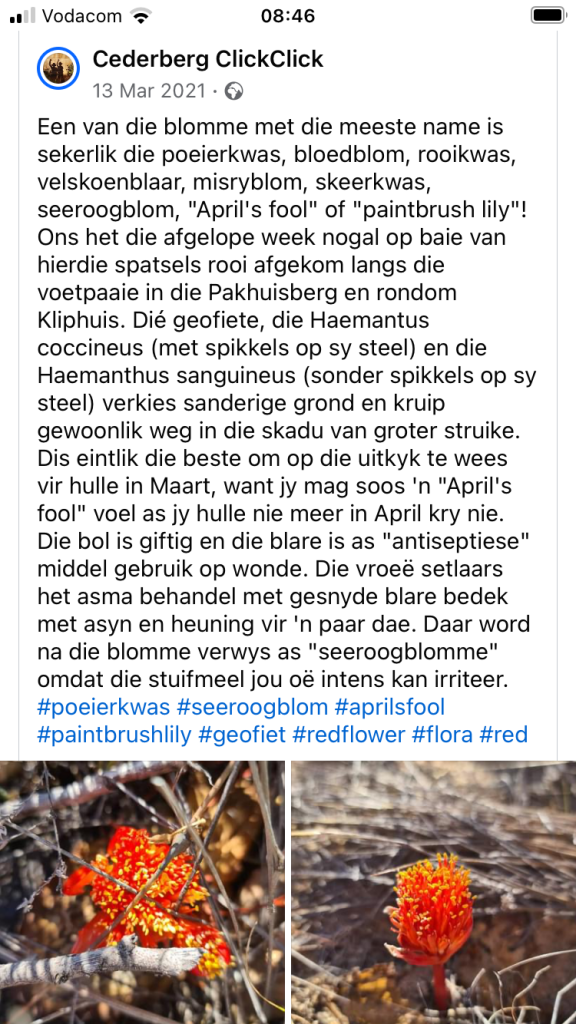

Soon after we saw a bright splash of red and yellow in an otherwise drab patch of veld, which turned out to be an unusual lily with several common names, one of which is Paintbrush Lily

By coincidence the same evening, while scanning through some wild flower posts on facebook, I came across an interesting post which went into some detail about this unique flower, in Afrikaans

We still had two days of relaxation ahead in this lovely national park, which tends to grow on you