Some two years ago I posted about a memorable swim at Santos Beach in Mossel Bay, the coastal town that is our home for a large part of the year. On that occasion it was a unique spectacle of nature as hundreds of terns and gulls gathered to feast on shoals of anchovies that had come so far inshore that swimmers could literally scoop them from the sea. (https://mostlybirding.com/2020/02/18/a-swim-to-remember/)

In early February this year we witnessed an even rarer happening in Mossel Bay, which started on Sunday 6th February 2022 on that same beach – Santos – and continued throughout the week, spreading to the harbour area and as far as the Point.

The Story Begins

From sunrise on Monday morning, small knots of people could be seen gathering at strategic spots along the shoreline of Mossel Bay, many dressed in bush clothing, with binoculars draped around their necks and carrying ‘weapons’ of varying size, the latter often covered in camouflage material designed to conceal them.

Their actions were strange – one moment they would be gazing out to sea or scanning the beach and harbour with their binoculars, the next moment they would be on the run to a nearby vantage point, hiding behind anything they could find and pointing their ‘weapons’ at the object of their interest.

At other times they would stand around talking animatedly, checking their phones constantly, then at some signal rushing to their vehicles and driving anxiously to another of the favoured spots, there to repeat the procedure.

At the harbour, a designated National Key Point in South Africa, the gathered groups encountered some resistance to their endeavours, as security personnel approached menacingly, ordering them to refrain from entering the harbour area and from pointing their ‘weapons’ in the direction of the harbour.

This led to several verbal skirmishes and the mood of the increasing number of ‘attackers’ seemed to take a turn for the worse. However a message, possibly from a ‘Central Command’, had the groups heading off to one of the other points and calm returned to the harbour once again.

This continued throughout the day and for the rest of the week, with the initial groups of ‘attackers’ being replaced on a daily basis by new groups arriving from all over South Africa.

What was Going on?

It could only be one of two things –

- the start of an armed insurrection, or

- twitchers gathering to see and photograph the latest addition to the Southern African list of birds

I’m glad to say it was the latter, especially as I was initially responsible for starting the scramble to see this first time vagrant to our shores!

And the ‘weapons’ referred to in the story above are, of course, the long-lensed cameras favoured by birders (the ‘attackers’) trying to capture an image of the bird for their records.

How it Happened

It all started with a trip to Santos beach with my daughter Geraldine and son-in-law Andre, for a late afternoon swim just after 6 pm on Sunday 6th February 2022. We parked and walked down the steps and across the grassy embankment towards the beach – ever on the lookout for birds, I noticed that there were about a dozen gulls in the fresh water pond that forms in the middle of the beach at the stormwater outlet, drinking and bathing at the end of a no doubt busy day of scavenging and resting.

As we got closer to the pond I stopped dead in my tracks, let out a mild expletive and said to Andre and Geraldine “That’s a Franklin’s Gull!” – it stood out like a sore thumb amongst the similar sized Grey-headed Gulls lined up at the pond, with its black hood and dark, slate grey wings contrasting with the mostly white head and pale grey wings of the similar sized gulls normally encountered in Mossel Bay.

This excellent photo (by Estelle Smalberger the next day) best represents the view we had of the gull at the pond

I had come to the beach for a late afternoon swim, so had none of my usual birding paraphernalia – no binos, no camera, not even my otherwise ever-present phone, so Andre dashed back to the car to get his phone. Geraldine and I stood and watched the gull intently while we waited but, as luck would have it, the gull finished drinking and bathing a few seconds before Andre got back and it flew off in the direction of the harbour.

I buried my head in despair for a few seconds, then shrugged it off and we enjoyed the swim we had come for.

Fortunately the gull had been quite relaxed and allowed us to approach within a few metres of its spot alongside the pond, so I was able to confirm in my mind the instinctive first ID of the gull as a Franklin’s Gull.

This was without any of the usual aids, simply based on having seen the species in Canada some years ago – the breeding plumage with full black hood and white eye crescents were what clinched it for me, without considering other possibilities……..I mean, no other gulls with a fully black hood occur in Southern Africa, so what else could it be ……. ?? (The Black-headed Gull, also an occasional vagrant, looks similar but its hood is a chocolate brown colour)

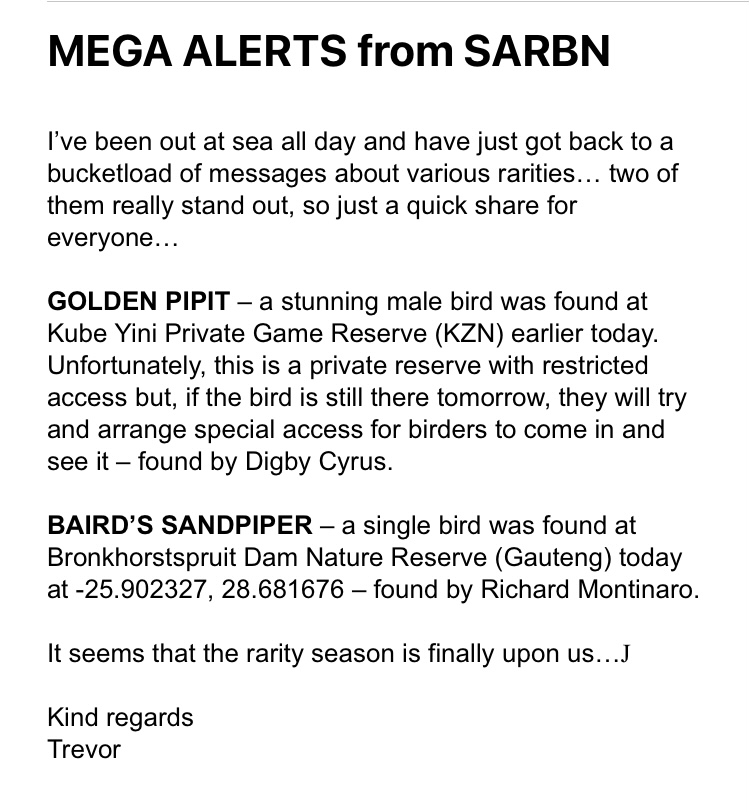

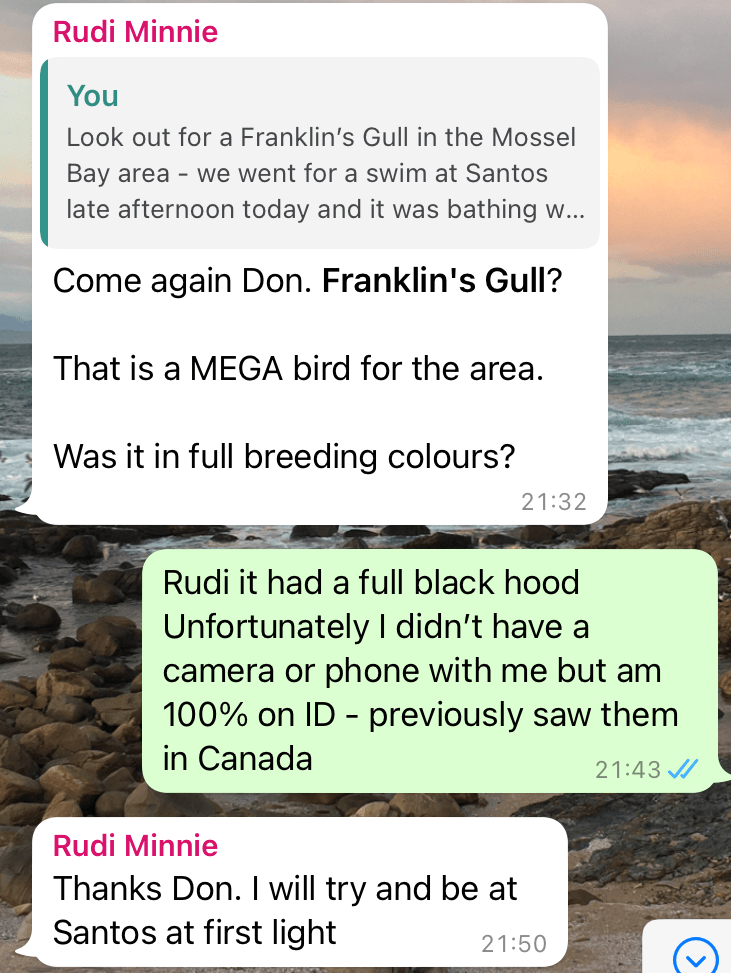

Once I got back home, I posted a message on the local birding whatsapp group, at 8.13 pm to be precise, suggesting that all keep a lookout for a “Franklin’s Gull” in the Mossel Bay area.

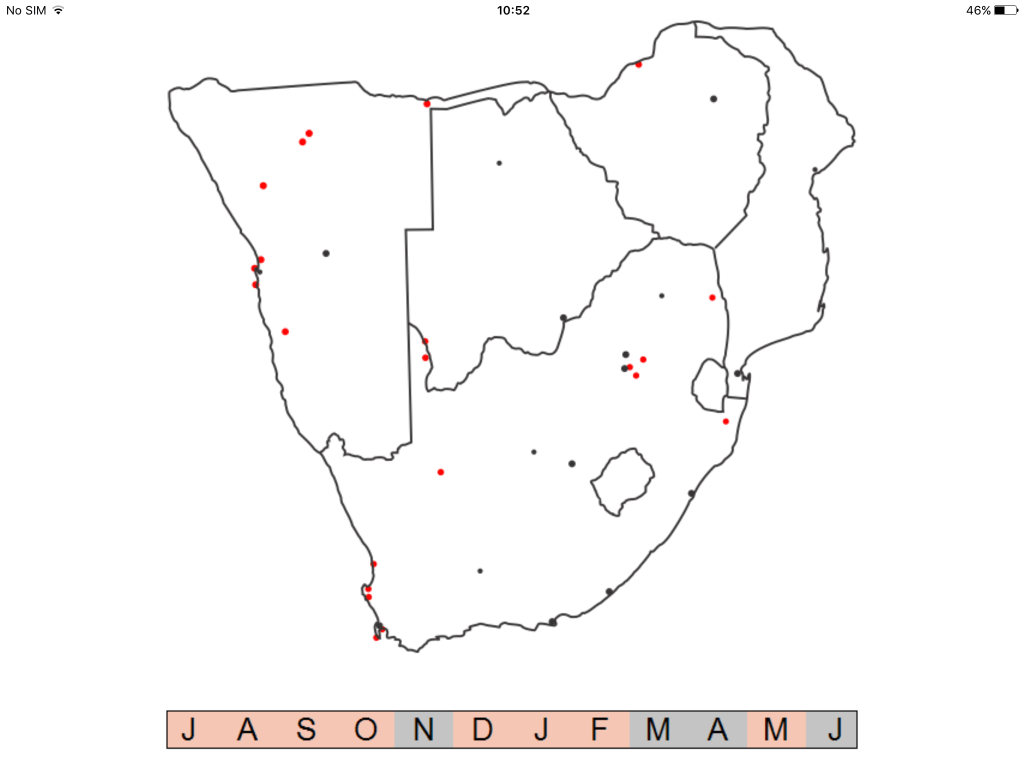

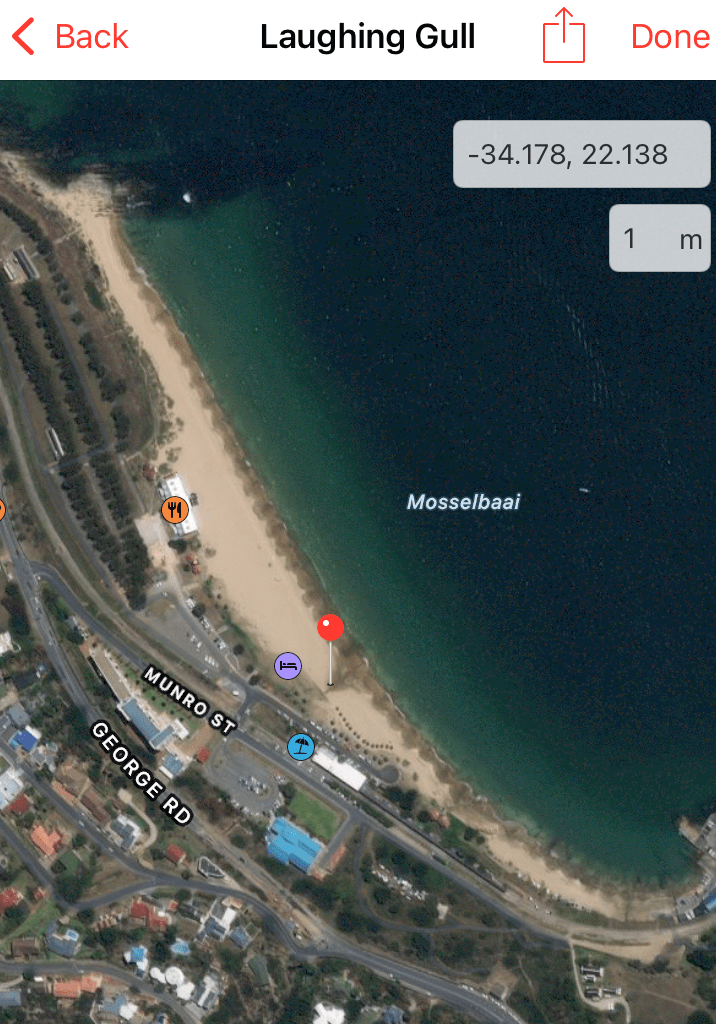

At the same time I recorded the sighting on my Birdlasser app which shows the location of the sighting on a map (this shows the corrected species name)

Some time later, at 9.32 pm, Rudi Minnie responded with some amazement and undertook to be at Santos beach at first light on Monday morning.

And there I left it, happy that I had spotted a rarity, one that is recorded only sporadically along the west and east coasts of South Africa and one that would no doubt be of interest to a few birders ……

Monday dawned sunny and warm and I headed out early to the Vleesbaai area where another rarity – a Baillon’s Crake – had been reported, my plan being to hopefully find it and atlas the pentad at the same time. While waiting patiently for the crake to put in an appearance (one juvenile popped out briefly, too quick for a photo) I kept an eye on the messages from those looking for the “Franklin’s Gull”.

First to confirm it was Edwin Polden at 6.42 am and Rudi Minnie shortly thereafter, followed by the first photos at 7.01am.

Some other Mossel Bay birders followed up with their own photos, providing more detail of the gull’s features

Trevor Hardaker, chair of the SA Rarities Committee and the undisputed ‘king’ of rarities in Southern Africa joined in the discussion, expressing his concern about the initial ID and imploring photographers to send a photo of the gull’s upper wing colouring. There was some speculation about his reason for this request, which became more urgent as the minutes ticked by.

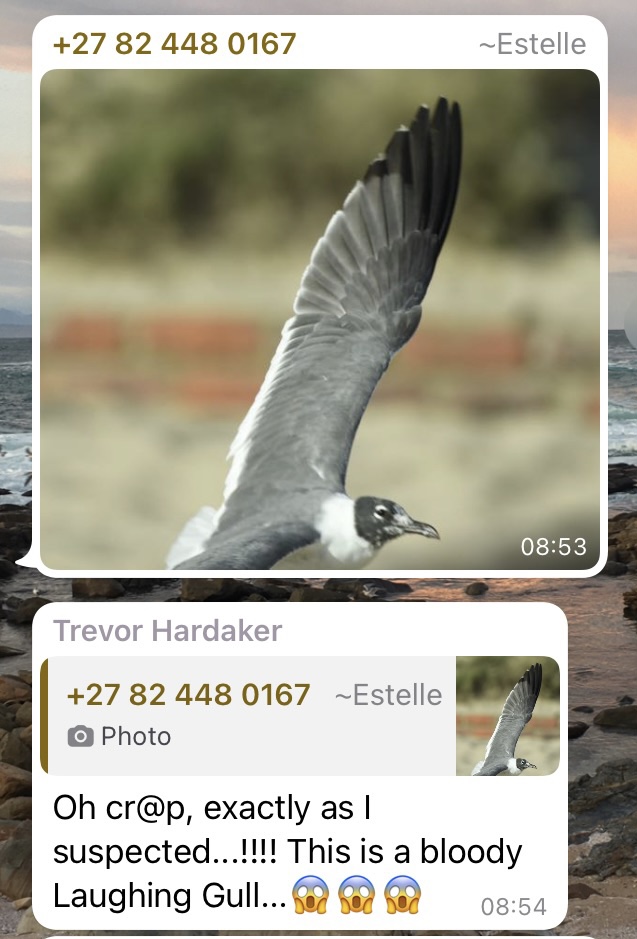

Fortunately Estelle Smalberger was able to post a photo showing the upper wing of the gull with all-black wingtips –

and the reaction from Trevor was instantaneous :

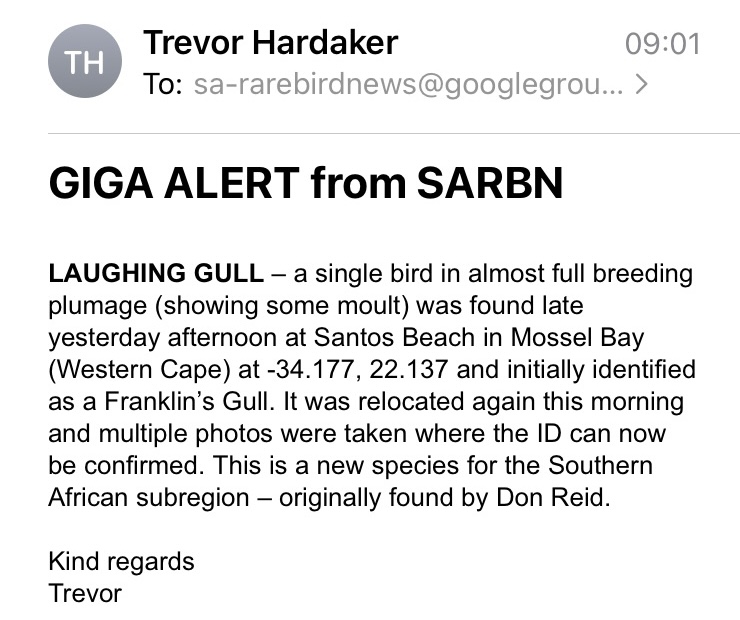

Some 7 minutes later Trevor sent an email alert to the thousands of subscribers around Southern Africa to let them know about this ‘Giga’ rarity, a new species record for the sub-region, which had many of them, including Trevor himself, re-arranging their lives to get to Mossel Bay without delay and hopefully see the gull.

Laughing Gull vs Franklin’s Gull

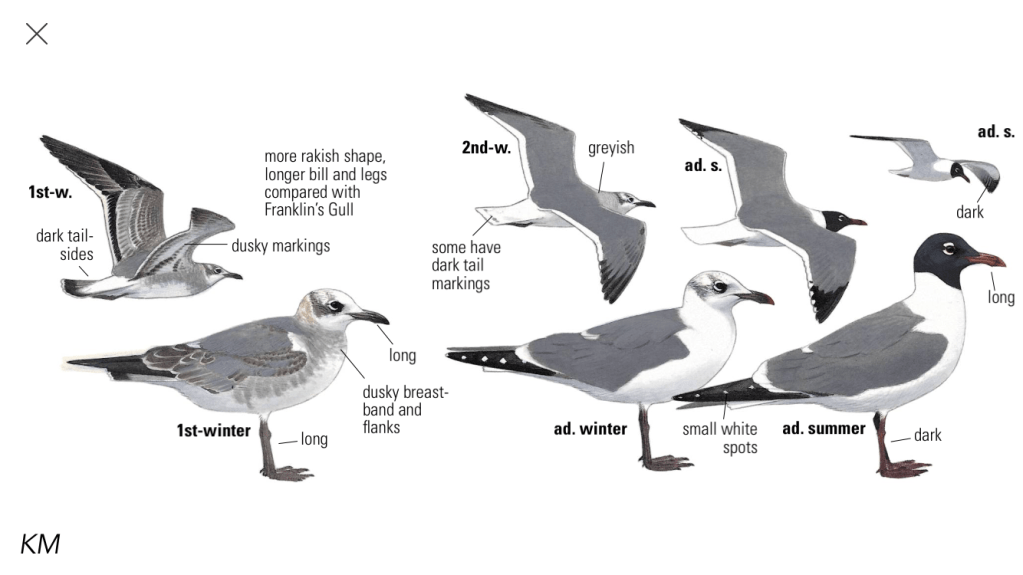

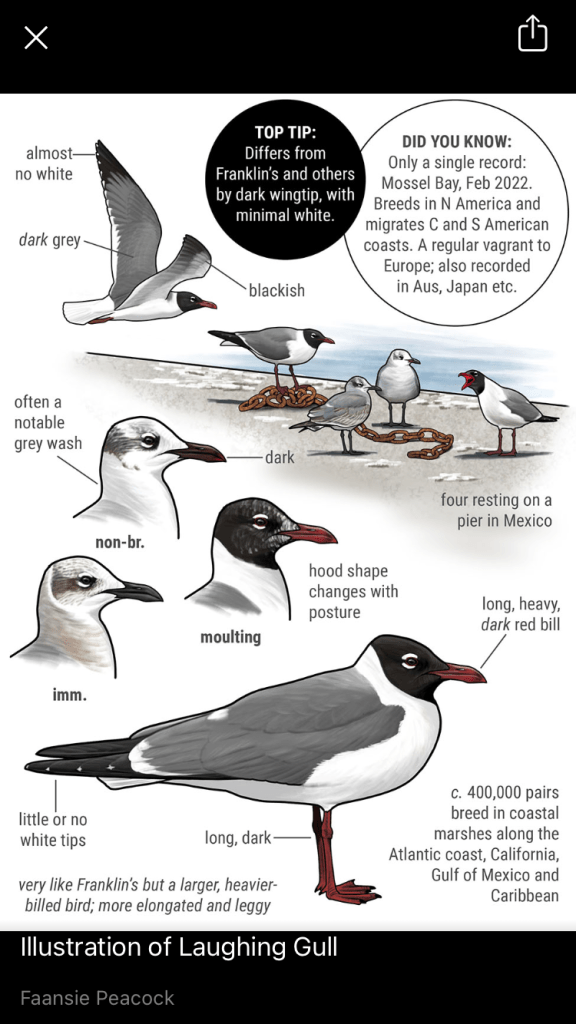

It took the expertise of Trevor Hardaker to correctly ID this gull and it was based on the differences in upper wing pattern which are nicely illustrated in these excerpts from a guide book which he posted

This is the Laughing Gull – (in non-breeding plumage so without the black hood)

And this is the Franklin’s Gull –

The Reaction

The reaction after Trevor sent out the alert was not unexpected – there are a number of birders in the region who will go to any lengths to add a species to their lists for the southern African sub-region and this new species presented a golden opportunity for the ultra keen twitchers. Some must have literally upped and rushed to the airport and found a seat on a flight to George, as the first arrivals from Gauteng were in Mossel Bay that same afternoon.

Others made quick arrangements and drove long distances to Mossel Bay from all over SA. This continued throughout the week, with clutches of anxious twitchers staking out the favourite spots and sharing messages until they too were able to ‘tick’ this new species and get a photo or two.

The gull became a celebrity visitor overnight and by far the most photographed bird in SA that week as several hundred birders descended on the town over the 6 days it remained there.

Here is a selection of photos posted on Facebook and Whatsapp groups –

I managed to get a few images of the gull when it was perched on the wall near the harbour

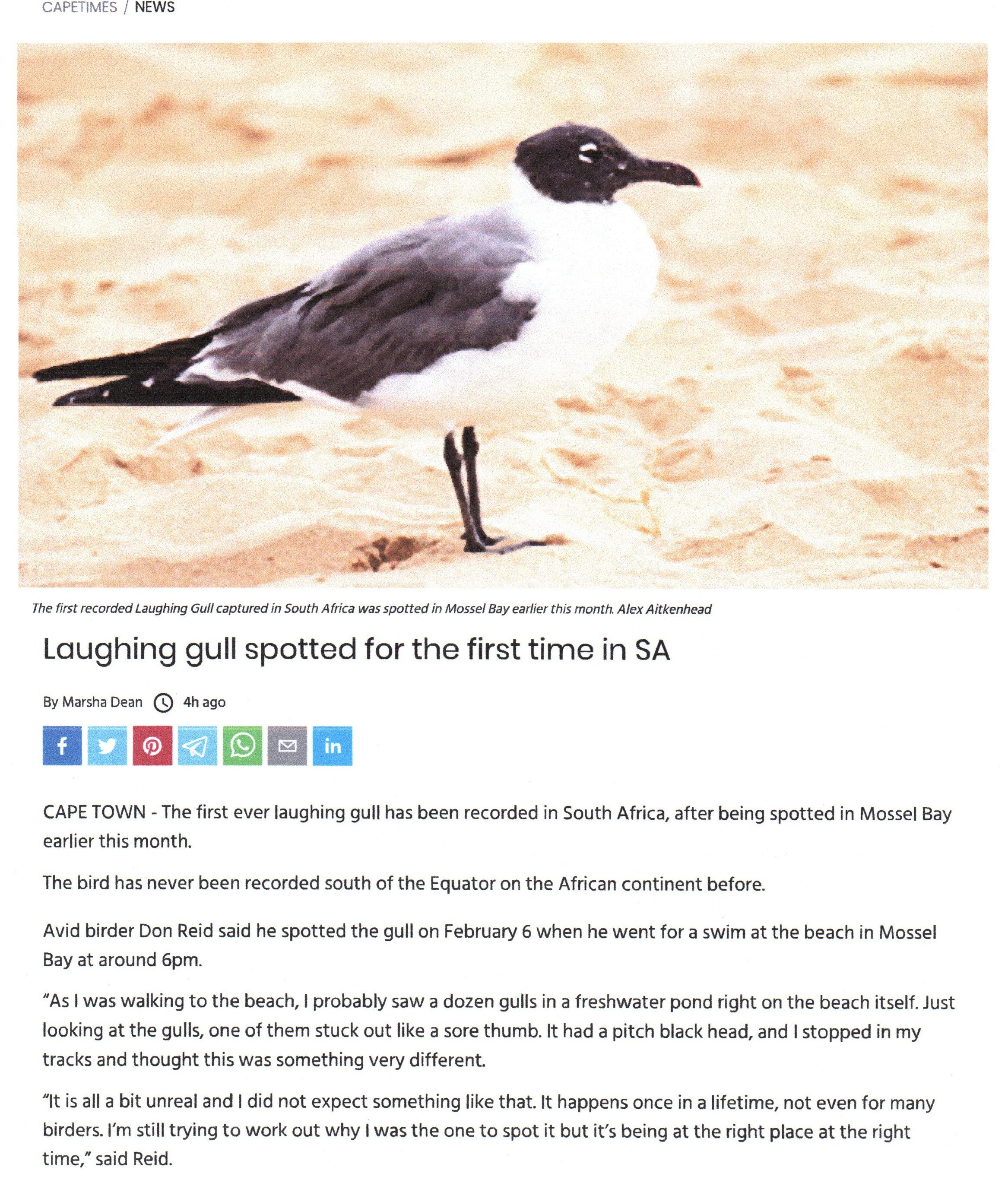

In The News

The presence of the celebrity gull soon spread to the newshounds and articles were published in several newspapers – at first the local Mossel Bay and George papers carried the story which then spread to the Cape Town newspapers. It even made the national SABC newscasts.

Laughing Gull Leucophaeus atricilla (Roetvlerkmeeu)

Laughing Gulls, named for their raucous call which sounds like a high-pitched laugh, are monogamous and form long-term pair bonds. They breed in large colonies from April to July on the Atlantic coast of North America, the Caribbean and northern South America.

They are coastal birds found in estuaries, salt marshes, coastal bays, along beaches (where I first found it) or on agricultural fields near the coast. My previous (only) sighting of Laughing Gull was on the Varadero Peninsula on the north coast of Cuba during a memorable visit some years ago.

Laughing Gulls are gregarious birds, noisy and aggressive in nature and don’t hesitate to steal the prey of other birds.

Topmost in many birder’s minds was the question “How did it get to Southern Africa?”. That’s an impossible one to answer but several ideas were postulated such as –

- there have been numerous previous vagrant records in the UK and western Europe so perhaps this was another which then proceeded to migrate south as it would normally do in its home territory and only stopped when it reached the southern end of Africa

- ship-assisted vagrants are not unknown so perhaps it hitched a ride on a ship that passed Mossel Bay, from either east or west and thought, as we do, that it looked like a rather nice place to spend some time

And that sums up the newest addition to the Southern African bird list. Trust Faansie Peacock to be the first to add it to his brand new birding app called Firefinch, due to be fully launched this year, already partly available

What a shame that the handsome Laughing Gull stayed in Mossel Bay for just a week – the following Sunday it was nowhere to be found…… who knows where it went next and whether this species will ever be seen in the Southern African region again.

But it had provided a lot of excitement for the birding community during its short stay!